The lack of available cash in the government’s kitty, the Conservatives’ occasionally frayed relationship with ‘business’ and the likelihood that Labour took on board Trussonomics’ lesson that unfunded promises could prompt chaos may all mean that investors could be in the mood to take Sir Keir Starmer’s big lead in the polls, and any eventual victory, in their stride, even if the FTSE All-Share’s record shows it seems to prefer a Tory government, on average.

The prospect of a government spearheaded by Sir Keir and Rachel Reeves is unlikely to spark the sort of fear that would have been inspired by an administration whose driving forces were Jeremy Corbyn and John

McDonnell. Moreover, the current Conservative government, whose tenure effectively dates back to 2010 and covers a flurry of five prime ministers, could be seen as having taken an increasingly interventionist approach to the economy, given such initiatives as sugar taxes, Help to Buy, energy price caps, windfall taxes on North Sea oil producers, 2021’s National Security and Investment Act and proposals for changes to the 2005 Gambling Act under the recent review.

Increasingly vocal and forceful regulators, such as the Financial Conduct Authority, Ofcom, Ofgem, Ofwat and the Competition and Markets Authority, appear to be responding to public pressure for greater action, and perhaps the hardest part for investors going forward will be spotting which industry or sectors will come under scrutiny next, in the wake of such recent examples as betting, funeral services and veterinary services.

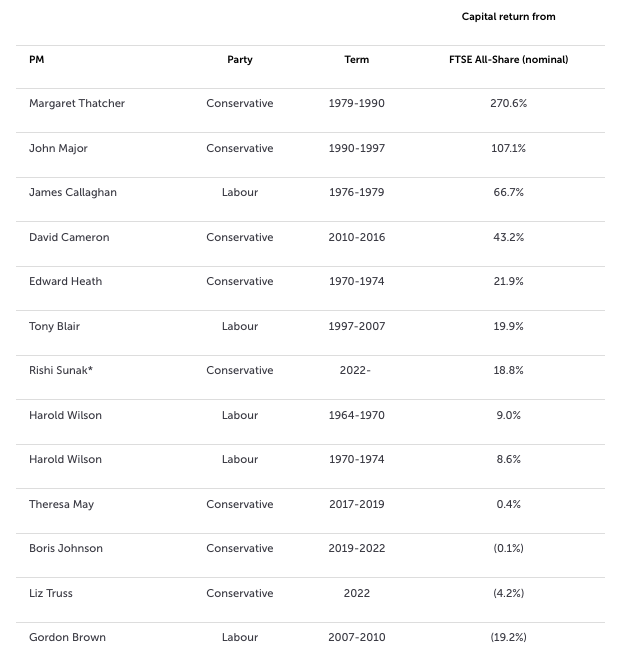

The headline data suggests that a Labour government, and a change in the identity of the incumbent in 10 Downing Street, need not be seen as an inherently bad thing.

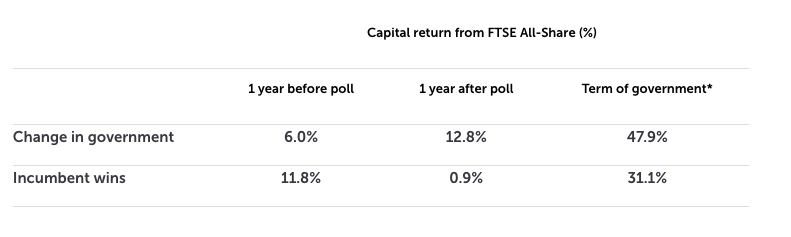

A study of all sixteen of the general elections since the inception of the FTSE All-Share in 1962 shows that the UK stock market is by no means frightened of a change in government and it may even welcome it. On average, the FTSE All-Share has recorded a double-digit percentage gain in the first year after an election which sees one prime minister ejected from office and another, new one ushered into it. There are also greater average gains when a government changes relative to when it remains the same.

Source: LSEG Datastream data. *1964/66 to 1970 Wilson governments and 1974/74 to 1979 Wilson/Callaghan governments counted as one term. 2019 Conservative government to 22 May 2024

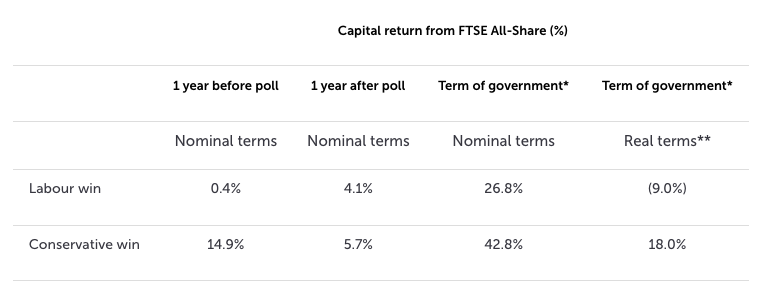

Labour governments can also point to healthy average stock market gains during the terms of their five prime ministers during the 42-year era of the FTSE All-Share.

That said, the UK equity market has done better since 1962, on average, when the Conservatives have triumphed at the ballot box.

Source: LSEG Datastream data. *1964/66 to 1970 Wilson governments and 1974/74 to 1979 Wilson/Callaghan governments counted as one term. 2019 Conservative government to 22 May 2024. **Adjusted for retail price index (RPI).

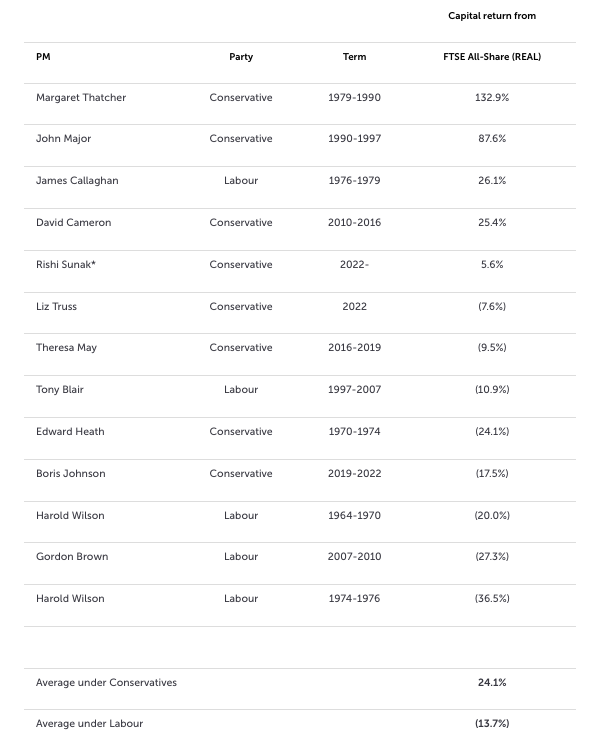

Some investors could therefore be forgiven for wishing for a Conservative government, on financial grounds, irrespective of their personal political preferences, especially as the average real, post-inflation return from the FTSE All-Share is markedly superior under Conservative governments than it is Labour ones.

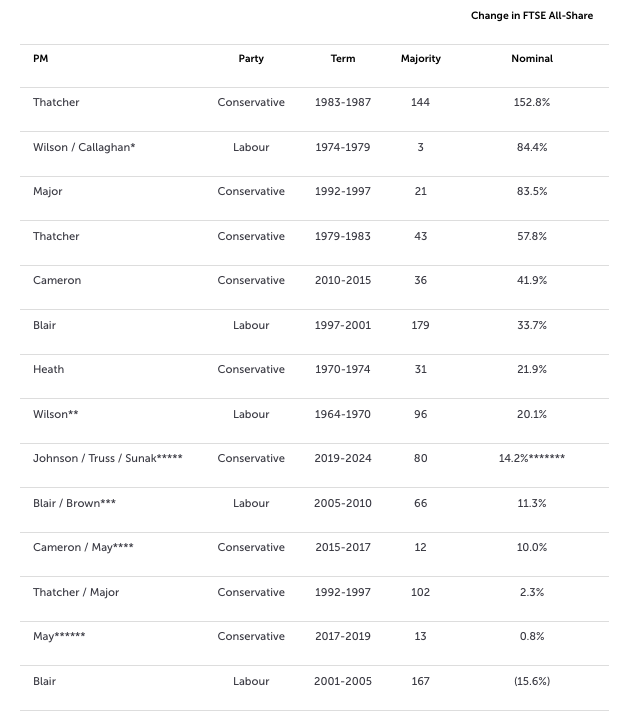

The size of a government’s majority seems to be matter of indifference to stock market investors, even if any incumbent in 10 Downing Street will be looking for a thumping advantage in the House of Commons, so they can get on with the business of governing the country and formulating policy, rather than having to constantly curry favour with their own MPs first.

Margaret Thatcher’s crushing 1983 general election win helped to set the tone for her second term and that period yielded the best nominal (and real, post-inflation) returns from the FTSE All-Share from any post-1962 administration. However, Tony Blair’s second-term majority was even bigger, and that period yielded negative returns for investors in UK equities, using the FTSE All-Share as a benchmark.

Source: LSEG Datastream data. *Wilson initially PM with a minority of 33 after February 1974 and then with a majority of 3 after October 1974. Wilson stepped down in April 1976. **Wilson initially won a majority of 3 in 1964 which was increased to 96 in 1966. ***Blair stepped down in June 2007. ****Cameron stepped down in July 2016. *****Johnson resigned in July 2022. Liz Truss took over in September 2022 and was replaced by Rishi Sunak in October 2022. ******May’s initial working majority was based on a deal with the DUP. *******Performance under current government as of 22 May 2024

Again, the role of inflation is important here. The 1974-79 Labour administration that began under Harold Wilson and ended under James Callaghan started off with a tiny majority but on paper generated healthy returns for the FTSE All-Share, which rocketed. However, once those returns take a spiral in the RPI measure of inflation into account (and RPI is used as it offers a longer history than CPI), then investors actually lost out in real terms, in what was a difficult decade for shareholders, owing to the ravages of inflation.

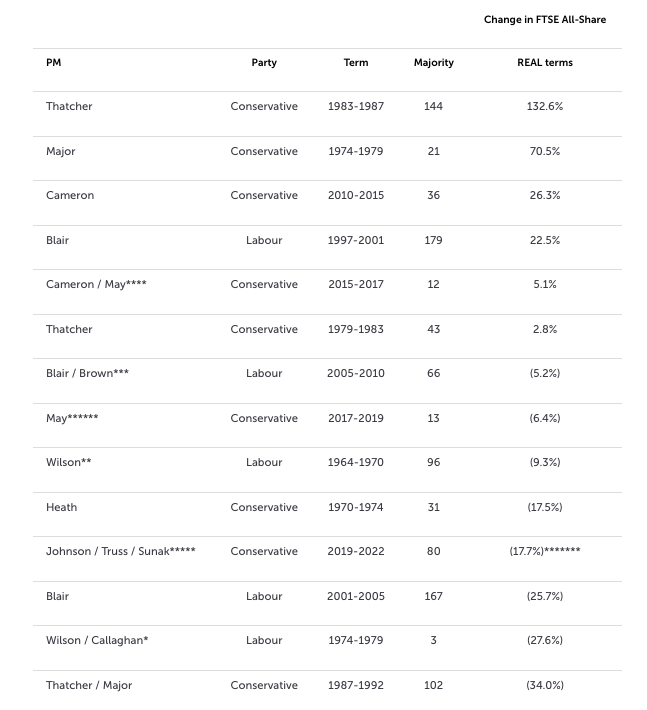

Source: LSEG Datastream data. *Wilson initially PM with a minority of 33 after February 1974 and then with a majority of 3 after October 1974. Wilson stepped down in April 1976. **Wilson initially won a majority of 3 in 1964 which was increased to 96 in 1966. ***Blair stepped down in June 2007. ****Cameron’s majority relied on a coalition with the Liberal Democrats. He stepped down in July 2016. *****Johnson resigned in July 2022. Liz Truss took over in September 2022 and was replaced by Rishi Sunak in October 2022. ******May’s initial working majority was based on a deal with the DUP. *******Performance under current government as of 22 May 2024

Inflation also sorts out the real winners and losers, from the markets’ perspective, when it comes to individual prime ministers. Of the 13 prime ministers since 1964, four of the best five from the very narrow perspective of stock market perspective were Conservatives, once FTSE All-Share returns are measured in nominal terms.

Source: LSEG Datastream data. *As of 22 May 2024

But the shake-out comes in real, post-inflation terms, when four of the five best premierships for investors came under the Conservatives and the three worst under Labour.

Source: LSEG Datastream data. *As of 22 May 2024

This is not to make an economic point, rather than a political one. As former US president Bill Clinton’s strategist, James Carville, argued ahead of the then Arkansas governor’s 1992 election win, ‘It’s the economy, stupid.’ If the voters feel flush, they are more likely to vote for the incumbent government and less so if not, and inflation is a key part of that.

The galloping inflation of the 1970s, and subsequent labour unrest, did for both Ted Heath in 1974 and James Callaghan in 1979. In the latter case, public appetite for a change of tack was particularly strong and ushered into power the nation’s first female prime minister.

Gordon Brown had little or no chance, having had the bad luck to preside over the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-09 and Tony Blair’s second term coincided with the bursting of the technology, media and telecoms bubble, the blame for which could not be laid at Downing Street’s door under any circumstances.

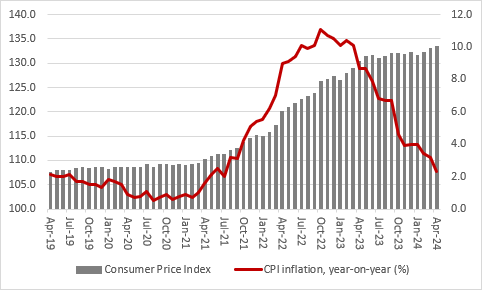

What will be interesting this time around is the degree to which inflation and the economy shape public thinking once more. The Brexit vote dealt Theresa May a difficult hand and the pandemic gave Boris Johnson a dud one, but the public will remember inflation and the cost-of-living crisis. Regardless of whether they blame that on the Bank of England’s monetary experimentation, supply chain dislocations caused by the pandemic, the oil price spike that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, or just stick it on the government may be a crucial factor in how the general election plays out.

For all that Rishi Sunak now feels able to claim the credit for a deceleration in the annual rate of inflation back to 2.3%, prices are still rising and not shrinking. Since Boris Johnson defeated Jeremy Corbyn in December 2019, the retail price index is up by 31.9% and the consumer price index by 23%, so the cumulative impact of inflation upon consumers’ spending power is damaging indeed.”

Source: LSEG Datastream data. *As of 22 May 2024

Leave A Comment