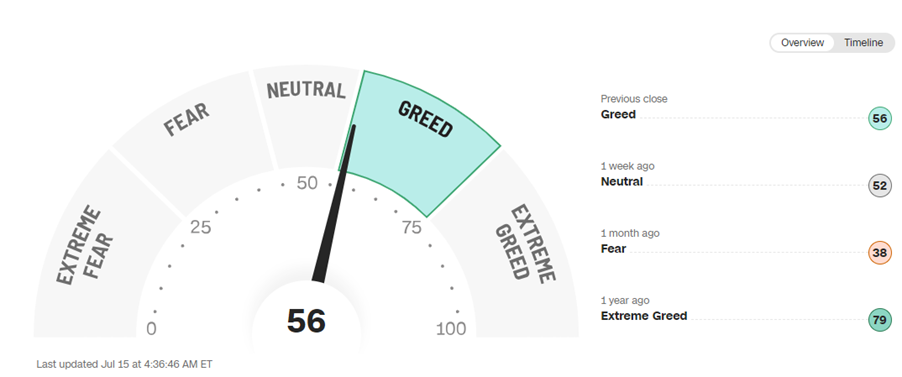

As you may remember, we have recently been showing the Fear and Greed Index, published by CNN Business, as a barometer of market sentiment.

The fundamental factors driving short-term market movements are these two basic human moods, with markets tending to rise when investors feel greedy and fall when they feel fearful.

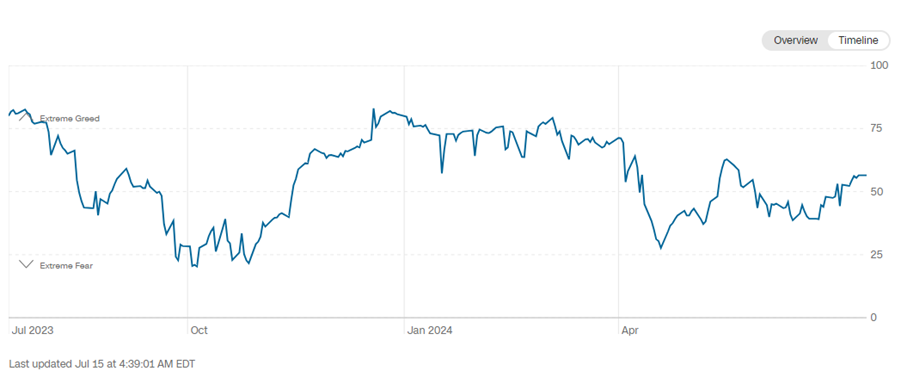

How has this rating changed over the last year?

As you can see above, sentiment has been fairly good this year, with not too many negative moments.

Why have markets been strong?

We have always talked about shares being a hedge against inflation. Real companies who own real assets, make real products and generate real profits and pay real dividends have an ability to cope with inflation that few other assets do. However, the typical response to inflation – higher interest rates – means that this does not happen at the same time. This year, then, despite a deteriorating economic outlook, has been one in which equities have recaptured some of the ground that they have lost over the last couple of years.

What about interest rates?

Across the world, inflation is falling back from peaks, albeit more slowly than anticipated. Europe has already begun to cut rates and the US and UK are expected to follow in the next few months. This creates a positive outlook for economic growth and for equity markets over the next few years.

Why is this?

Lower interest rates have a number of impacts. From a consumer level, they lead to lower mortgage and borrowing costs, which tends to boost spending. At a corporate level, investment decisions made by companies become more viable, as funding becomes easier. Finally, they are very positive for governments who, over the last couple of years, have seen the cost of servicing their debts rise dramatically and who are prioritising growth.

Ah, politics!

Well, it didn’t take too long to get to politics in a year that has been – and will continue to be – dominated by elections. In a six-week marathon, India re-elected Narendra Modi as Prime Minister, but with no overall majority. Elections for the European Parliament indicated a shift to anti-EU, populist parties and this was quickly followed by the decision of Emmanuel Macron in France to call a snap election. The result? Political paralysis in France as the Left, the Right and the Centrists all received around a third of the vote and no desire of any party to go into coalition with any other.

And the UK?

On the face of it, the election result was a stunning victory for Keir Starmer, but under the bonnet, things look a bit different. A splintering of the Conservative (and, to some extent, Labour) vote between minority parties, the collapse of the SNP in Scotland and the vagaries of the ‘first past the post system’, meant that Labour’s record majority was achieved with just over a third of the votes cast. The combined total of Labour and the Conservatives of 57.4% was the lowest since 1918 and highlights, perhaps, a dissatisfaction with any established party – something seen across the world.

What will Labour do with this majority?

Given that the majority is not necessarily what it seems in terms of its permanence, we suspect that, rather like the first Blair administration, the focus will be on demonstrating competence and getting re-elected. This will be easier said than done, of course, as they face an overflowing in-tray of issues. Headline tax rises were discounted in their manifesto, but there are bound to be tweaks to allowances and exclusions, as the government tries to find funds to boost spending in their preferred areas. Nevertheless, like most governments, growth and trade are likely to be a key area of focus.

What about the US?

The shocking events at the Trump rally in Pennsylvania, coupled with some less than convincing performances from Joe Biden, left Donald Trump as very much the favourite for the White House and raised concerns further ‘down the ticket’ that the Democrats could lose any control of Congress. Biden’s forced resignation and the rapid anointment of Kamala Harris may not change the eventual result of the Presidential election, but the wider results are now more uncertain than a few days ago. Whoever wins, however, is likely to inherit a US economy which, while slowing in parts, will still be home to a vibrant and innovative technology sector. This, in turn, will underpin the US domination of the global economy, although challenges from China and the emerging world will continue.

Isn’t the IT sector a bubble waiting to burst?

We would argue not. True, there have been some very strong returns from technology companies, especially those with exposure to Artificial Intelligence. However, these returns have not been built on hope and expectation, but rather on surging sales, strong profits and the prospect of more to come. Despite the price rises, many of the companies have long runways for growth, as the upgrade cycle for technology continues to gather pace. Not all companies are immediate winners – some software companies have spoken of deferred spending as companies shift their IT spending to computer hardware.

How important is the IT Sector?

IT – a very broad term – is far more pervasive in the global economy than it has ever been. Semiconductors, Internet, Software and Computers together account for around 34% of the MSCI World Index and this is just companies that are specifically involved in the sector – not companies like Amazon (it is classified as a retailer) and Meta, owner of Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, which is classified under Telecommunication services. Indeed, arguably almost every company is an IT company these days as, in most business areas, those companies that do not invest in their systems will quickly be overtaken by those that do. In that sense, it is really just a continuation of a series of technological advances that started with the industrial revolution. But that has perhaps quickened in pace this millennium.

Will advances in AI be that significant?

This is the big question! At one level, it is likely to boost productivity as companies can automate and streamline their operations, cutting their costs and improving their profitability. At another level, it is not likely to lead to a vast number of new jobs – quite the opposite in fact. To some extent, an ageing population and shrinking workforce will play into this, as more people drop out. However, it is also likely that semi-skilled and skilled jobs will be automated, leaving a population that becomes more marginalised and less prone to support existing political systems.

Where does that leave the outlook for the rest of the year?

It is worth pointing out that none of these changes are going to happen instantaneously and that very few things move in straight lines. After a strong first half, it would be natural for global markets to consolidate a little, although an environment of falling interest rates is likely to be positive for most asset classes – not just equities. In addition, as we move through the year, some of the political uncertainties will begin to fade into the background and businesses and individuals can make longer term plans with less worry.

How are we positioned?

As we always highlight, investing in global markets involves taking a degree of risk. We can do the forensic work of ensuring that the quality of portfolios remains high and that we are invested in the kind of companies that will survive these changing times, but we cannot completely remove the volatility of the market which, roughly one year in four, will be down and, occasionally, substantially so. We have no real reason to expect any such trauma in the next year, but few – if any – predicted a global pandemic and the ensuing economic tsunami that was unleashed. We remain confident, however, that this focus on the quality of the investments that we hold will deliver solid returns over the longer term and deliver the results that we are seeking.

Leave A Comment